DENY EVERYTHING

The Life and Crimes of Joseph Marmion SJ

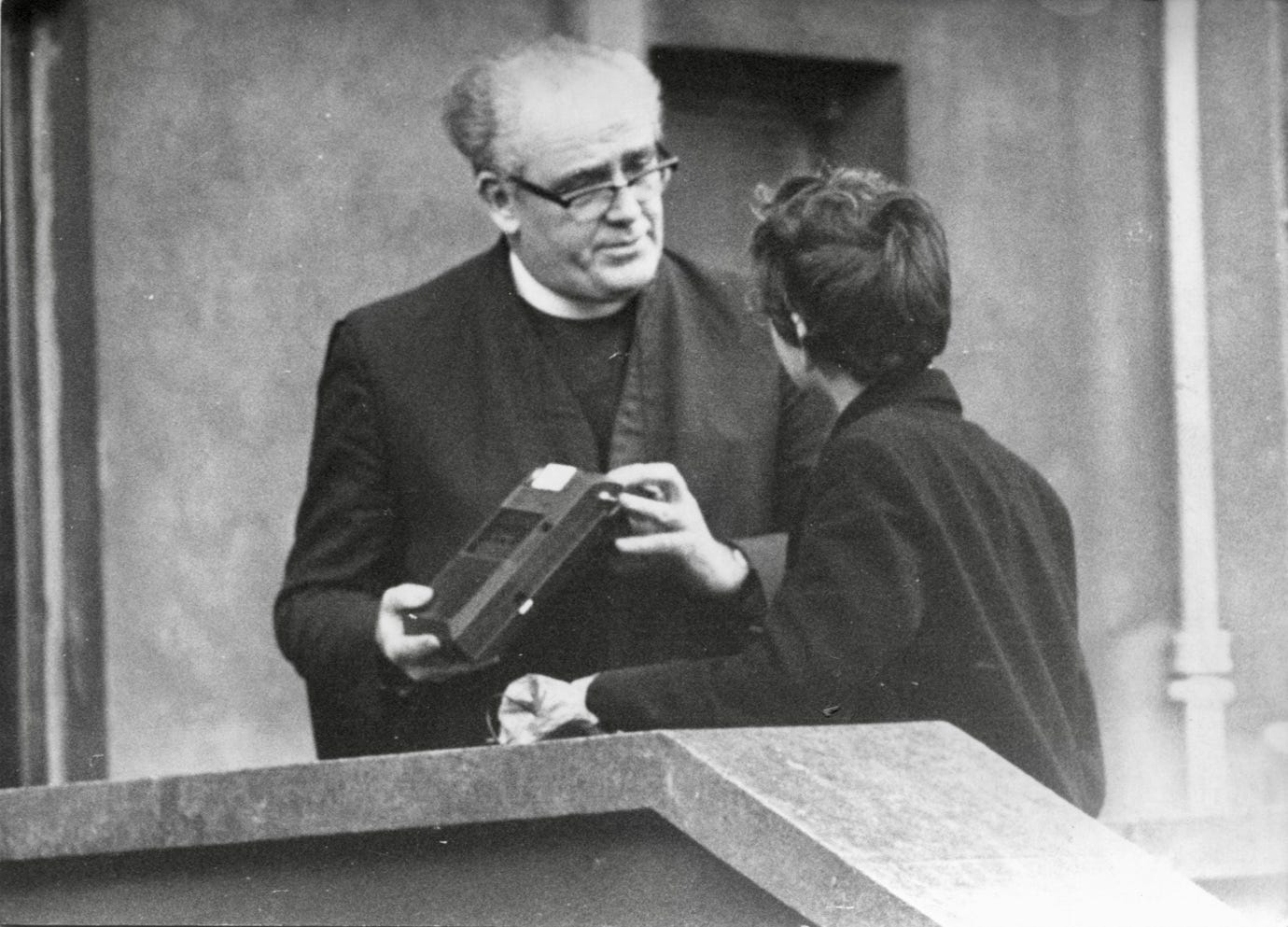

Photo: David Barry, by kind permission

INTRODUCTION

During the first few days of September 1977, I was bored. Aged 18, and with weeks to go before I entered Trinity College, Dublin I was missing the companionship of friends, with all of whom I had shared an education at Belvedere. Those who, like me, had left, were scattered around Dublin and beyond, and those who hadn’t had, for the most part, risen from Poetry or fifth year, to Rhetoric at the top of the school. Those who chose to repeat the Leaving Certificate at Belvedere rather than at the Institute of Education on Leeson Street or at Ringsend Tech, were in a small class called, without any intentional irony, Philosophy.

Dublin was smaller in those days, almost claustrophobic. The same could be said of the country at large. There was one legal radio station, one television station. Buses were yellow, the DART was still seven years away. Divorce, abortion, homosexual acts between consenting adult males, the import and sales of condoms were all outlawed. The institutions misleadingly known as mother and baby homes were doing good business.

On the sunny afternoon of Friday, 5 September, I took a number 11 bus into town and wandered into Belvedere as the inmates were being released. Belvedere was, and still is, a kind of island of privilege in North inner city Dublin. Centred on a fine Georgian townhouse dating from 1775, most of its business was conducted in redbrick blocks and in the brutalist 1970s Kerr Wing.

Chatting with some of my newly elevated Rhetorician friends, I noticed, standing in his usual spot, leaning on the low wall by the Junior House steps, Fr Joseph Marmion SJ. The fact that my friends and I had called Marmion The Turd for the previous few years will convey some idea of how much we detested him.

Marmion was surrounded, as usual, by a handful of senior boys whom we, rather unfairly, referred to as his acolytes. He may have been a monster, but he was a charismatic monster for many. His particular favourites we called, even more unfairly, his catamites.

He was relaxed, leaning back casually against the wall engaging in chitchat, almost certainly making disparaging remarks about some of his colleagues as they crossed the schoolyard from the Senior House to Belvedere House. No doubt he was also taking the opportunity to eye up the little boys who had just arrived in First Grammar, the most junior year in the Senior House. He had a taste for 13 and 14 year old boys. Nothing had changed.

But change was coming, the very next morning. His career as a teacher would be effectively over, he would be relieved of his rôle as producer, director and, effectively, dictator of the College operetta. His career as a bully, a sadist and predatory paedophile was about to come to an end.

Well, almost. Wings clipped, but as arrogant, narcissistic and self-serving as ever, he would remain on the teaching staff for the rest of that academic year. Outrageous and extraordinary as this may seem now, his immediate dismissal from teaching was considered to put the reputation of the school, and of the Jesuit order, at risk.

It would be too easy, and too convenient for some, to focus on Marmion in isolation. At the time of writing – October 2023 – a total of 44 Irish Jesuits have been credibly accused of child sexual abuse, one being Marmion, another Paul Andrews SJ. It is bizarre that Andrews was not mentioned in The Jesuit Response. It’s a fact that Marmion operated within an organisation that harboured others who shared his proclivities. Context is needed. Until the Jesuits name these men, it is simply not possible to extrapolate the full story. And, until then, it is convenient for the Jesuits to say – in effect – that nobody amongst their number knew what Marmion was up to.

And because Marmion’s sexual exploitation of boys was so egregious, it is all too easy to lose sight of perhaps his greatest crimes: the emotional and often violent physical abuse of boys. He was somebody who should never have been allowed to have contact with children. And the Jesuits knew that from a very early stage in his career. That they failed to act to protect children, at every opportunity, every cue, is beyond shameful.

This is my attempt to tell the story of Joseph Marmion, of those who protected him, even after death, and of some of those whose lives he damaged and, in some cases, destroyed. I have done my best to be fair to all those involved, even to Marmion himself.

Tom Doorley

October 2023

Acknowledgements:

Most of those whose assistance was invaluable in researching this story prefer to remain anonymous. I want to thank Donal Ballance, Joe Douglas, David Barry, Riocard O Tiarnaigh, the late Professor Fergal Hill, Roberta Doorley, Mark Byrne, Maurice Dockrell, Saoirse Fox, the Irish Jesuit Provincialate, The Library of Trinity College Dublin, the National Library of Ireland, the Public Records Office Kew, the Imperial War Museum, Liverpool Public Library, Mrs C Barker of St Francis Xavier College Liverpool, Dom Anselm Cramer OSB of Ampleforth Abbey.

Copyright 2023 Tom Doorley

Chapter One: A STORY EMERGES

In March 2021, unaware that the Jesuits were about to reveal that Joseph Marmion SJ was a predatory paedophile and a violent bully, I wrote about him in the Irish Daily Mail, having first mentioned him in a book of mine that was published in 2004. I was prompted to do so after a former teacher at Terenure College was convicted of the sexual abuse of boys. Why, I wondered, had Marmion got away with it?

At the time, I knew only a fraction of what I know of him now and I had spoken with only a handful of people who – in the words of one of them employing grim humour – had passed through his hands. Some of the details related here were not entirely correct but the gist most certainly was. I should stress that his ability as a teacher is disputed; few believe that he was brilliant.

This is what I wrote as the Jesuits prepared to name him:

“On a fine afternoon in June 1977, I walked out of my school for the last time as a pupil. I had just sat my Leaving Cert economic history exam and I'd been the only candidate. The place was eerily quiet as I headed towards the big iron gates and suddenly saw the outline of the school bully looming towards me, silhouetted against the sunshine.

“This was not a boy; it was a Jesuit priest and a predatory paedophile. During much of the 1970s he had bestrode the school like a priapic colossus and everyone - including, as I know now, many of his fellow priests - lived in fear of him.

“A few years ago, I tried my hand at writing a novel set in a very familiar school, featuring a familiarly monstrous teacher. Aspiring novelists are told to write about what they know. I named this character Father Oliphant, after a long-vanished shop on Drumcondra Road; it sounded vaguely exotic, like his own surname.

“And, although he is long dead, I'm going to call him Father Oliphant here. He had nephews in the school, all of whom were very pleasant and obviously blameless boys, at least one of whom had a very hard time because of his accident of birth.

“Anyway, Oliphant approached and I realised, once again and vividly, that I hated him and that he no longer had any power over me. I looked straight ahead, and walked past in silence.

“"Thomas, I saluted you," I heard from behind me.

“My stomach turned over and my heart started racing. Somehow, I managed to turn around and face him for a moment.

“"I know you did," I said, and walked off.

“I can't remember when I stopped trembling.

“In the wake of the McLean conviction and the revelations about this serial abuser's activities at Terenure College, I said on Twitter that we had had our own monster at Belvedere in my time. Over a dozen people contacted me to share their memories of what had happened to them and to their friends.

“My dismissal of Oliphant on that last day of school felt terrifying at the time, but I was one of the lucky ones. Yes, I ascribe my lasting phobia of reading in public to him and he did write a message in felt-tip on my bare chest in front of the class when I was fifteen. But I got off very lightly. For a long time he seemed vaguely to like me but, not in "that" way. As I got older, I recognised him for what he was: a bully to everyone and a very particular menace to the little boys who formed the "female" chorus in his annual Strauss operettas.

“When anyone who had been at Belvedere in the 1970s read the newspaper reports of McLean measuring young boys, stark naked and alone, for costumes that never fitted properly, we instantly recognised this gambit shared by the two paedophiles.

“Oliphant was large by any standards - his hands, of which he was very proud - were like hams, his head the size of a pumpkin, although mothers would sometimes say that he was a fine looking man. But when you were in First Grammar - first year in the arcane nomenclature of Jesuit schools - he could block out the sun, literally and metaphorically.

“A talented linguist, a brilliant teacher, he was immensely clever, and could call on limitless reserves of charm when he wanted to. In that cynically subversive way that can be so attractive to teenage boys, he would speak slightingly of other teachers and even impute pederastic tendencies to several blameless men, one of who he used refer to as "Mary", often in his presence.

“The testimonies of those men who, when they were twelve or thirteen, underwent Oliphant's costume measuring routine are all essentially the same.

“Conor (not his real name) recalls "He would take you, on your own, up to this room full of old clothes and there was a screen in the corner. And he'd tell you to strip, underpants and all, and when you were completely bare and feeling really bloody awkward and embarrassed, he'd help you on with a pair of tights - like nylons - and you could see everything through them. And then he'd tell you to stay there, sitting on one of those grey, plastic chairs while he went behind the screen for what seemed like ages. And it was obvious what he was doing there because he'd emerge all sweaty and kind of flustered and tell you, a bit sharply, to get dressed. But I don't think he ever actually touched anyone's genitals. At least, I never heard that."

“Tim (again, not his real name) told me: "The little fellows' chorus was divided in two and to put it bluntly, the pretty kids were chosen to be 'girls' and the plain ones, like, me got to be boys. It was the pretty kids that got measured."

“Conor, again, recalls "It just felt weird, sitting there, starkers. But when you're twelve and you're new to the Senior House, you think, well, maybe this is just normal here. And now I realise he was looking at me from behind that screen while he pleasured himself. I feel sick, to be honest."

“"It was all about power," Luke (not his own name) told me. "I had a good voice in first year and I have this memory of being alone with him doing scales and it was dead quiet, after school. Suddenly he spread his hand out on the table and it was huge. And he said put your hand on top, and I put my tiny hand on his. He didn't say a word but he didn't need to. It was 'I'm big, you're tiny, and I have all the power.'".

“This was a common experience.

“The favoured boys in Oliphant's German classes would be invited to spend a few weeks in August in Vienna. Usually they would be required to go through Confession with him. Darragh (not his real name) recalls: "When I was in first year an older boy told me that if Oliphant asks if you masturbate you say 'I don't know father, but I'll ask my parents.'" Darragh used this ploy and was left firmly alone.

“In Vienna he would tell boys "masturbation is a sin, but not if you do it in your sleep". On the pretext of "checking for a rash" he had Keith (not his real name) strip in his room for a thorough examination. "He said I seemed to have a tight foreskin and that I should try to loosen it. I remember he was wielding a tube of Savlon and I had to think really fast. I said 'wouldn't that be masturbation, Father?' and there was a silence for a minute and he said, yes, maybe I was right."

“It was in Vienna that the most sinister part of the Oliphant saga unfolded. He was constantly alert for any sign of a cough or cold or a temperature, which some, but not all, remember as being checked rectally. Two of the boys on whom he had preyed told friends that on the pretext of some mild or imaginary illness, they were required to sleep in Oliphant's room. They were given "medicine" and have no recollection of the next 36 hours. It seems likely that others went through the same ordeal.

“Keith told me "I'm still amazed that after what I'd experienced, I went back the next year. Somehow it felt better to be in the inner circle, to be approved of, instead of outside, where most people were. It made you feel special, which is, frankly, horrifying".

“Another, who preferred not to talk in detail about his experiences, told me "That bastard couldn't get enough of me. He tried to sleep with me in Vienna."

“On the very rare occasions when a boy dared to challenge what Oliphant was doing - and very, very few had the courage to do so - his response was always the same. "I'll deny everything".

“Whenever a boy was summoned from one of his classes to see the Headmaster he would always say, jokingly, "deny everything".

“Keith told an older boy what had happened to him and the response was, "if that gets out, you'll have to leave the school." And as Keith says, "he was just a kid, but it was terrifying".

“By the start of the Autumn term in 1977, matters were coming to a head for Oliphant. One boy, who had not been abused, reported the conversations he had had with those who had been. One of them was Keith who was summoned by the Headmaster and asked if the story was true.

"And of course, I panicked. I did exactly what he always said. I denied everything".

“Another boy who was questioned told me: "Look, it was good that I probably would have been believed. I know that now. But I was thirteen and I was scared of that bastard and I was scared that I'd get into trouble, that I'd be seen as doing something wrong. So, yes, I said it wasn't true. There was always this sense of menace when he was in the room. Actually there was a sense of menace when he wasn't there. You just had to think of him."

“I used to wonder how it took the school so long to take action but now I think I know. Such was this man's hold over virtually everyone, that boys lied for him. But it seems that the Headmaster had the wisdom to see through this. He placed "Mary" in charge of the opera, with Oliphant reduced to playing the piano. At the end of the academic year, he was sent to Gardiner Street parish as a curate, still uncomfortably close to the school.

“The boys who had accused him were told to report any further bullying or inappropriate behaviour and none, it seems, occurred.

“"He would still stand in the corner of the schoolyard, preening himself, against the Junior House steps," recalls one of those he had abused. "And a few acolytes still stood around him. But everyone knew he was finished. It was around that time that we started calling him The Turd. How's that for revulsion?"

“Keith recalls having to face him every day after being abused.

“"I have vivid memories of him in English class spending a disproportionate deal of time during Macbeth lessons on the theme of Jesuitical casuistry, the irony of which will not be lost on anyone. I do remember a favourite quote of his was actually from King Lear “As flies to wanton boys are we to the gods; They kill us for their sport.” You’re left wondering who were the flies and who the gods in his particular scenario."

“There is no doubt that he destroyed lives. One boy was so badly bullied in class that he could never recite a poem or speak in public. "That man ruined my teens and my twenties. I will tell you what he did to me, but please don't write about it."

“He was violent too. It was said that he had kicked down a door and broken a boy's jaw when he was teaching at Clongowes. And it was rumoured, when he suffered a fracture in the early 1970s, that he had been beaten up one night by four of his former victims from there.

“When I was fifteen I found a first year crying outside the music room and I asked him what had happened. Oliphant had not taken kindly to a remark and had literally thrown him out of the class. He had landed where I found him in a mess of dust and tears. He became a great friend and Oliphant would direct his laser-like stare at us in the yard, but we revelled in it. He hated to see older boys talking with younger ones. He feared what would be revealed about him.

“This friend died young and I recall saying to his mother who, in turn, became a great friend, that I had the gift of these great friendships to thank the monster for.

“It is said that Oliphant caused at least one suicide, several instances of alcoholism, drug abuse leading to homelessness in one case, and, in the words of one survivor, "plenty of mental scars that will never go away. He gloried in cruelty. Do you remember he'd always identify the shy, quiet, vulnerable boy in each class and then he'd regularly say 'go on, get so-and-so' and, God forgive us, we would? And at the time we thought it was just horseplay but God almighty, just think of what that did to people."

“The people with whom I spoke were all survivors, ones that somehow got through the varying degrees, and kinds of abuse. Most of them are conspicuously successful in their fields, high achievers.

“I asked one of them why this was. "Maybe it's because we just couldn't bear to let that fucker win." I'm sure that's true, but I know that some fell by the wayside.

“One old school friend of mine asked me why I was writing this. I said I just wanted these stories told. These events happened the better part of half a century ago but they need to be known.

“"You know he groped my scrotum" he said. "And to her dying day my mother used to say that there's never been a whiff of scandal about the Jesuits! I didn't disabuse her."

“This Jesuit died in 2000, aged 75, shameless to the end.”

I, and those with whom I spoke at the time I was writing this newspaper piece, loathed Marmion. For most of us, it was pure hatred. This is problematic because those of us whose lives he affected when we were children find it hard to acknowledge that Marmion, who we knew physically and in every other sense, as huge, was once a little boy.

There were, of course, those who seemed to like him, at least at the time. Some have spoken of how it felt to be approved by Marmion, to be part of a group that had his imprimatur, in a sense. Some, as Marmion himself recounted, kept in touch with him after they had left school. These people, as far as I can gather, were a very small minority.

And so, I set out to find out as much as I could about his origins.

Chapter Two: THE EARLY YEARS

Two things are terrible in childhood: helplessness (being in other people's power) and apprehension - the apprehension that something is being concealed from us because it is too bad to be told.

- Elizabeth Bowen

One thing of which we can be certain is that Joseph Ignatius Hayes Marmion was born in Liverpool on Tuesday, 24 November 1924, the third child of Dr Joseph Aloysius Marmion and Brigid Josephine Marmion, née Hayes. His birth was registered, including the name Hayes which he later dropped, in January 1926.

The Marmion family had moved to Roselands Cottage on Woodlands Road in the Liverpool suburb of Aigburth in 1924. Before that they had been living in Dodge Street, much closer to the city centre and in an area that was far from salubrious.

Given the move to Aigburth a few years later, it seems that Dr Marmion had been casting around for a suitable practice. The Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine was the first such specialist institution in the world, founded in 1898. The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine opened the following year and this is where Dr Marmion had spent some time in post-graduate training. It is possible that he may have worked at the Liverpool institution until an opportunity arose in general practice.

Joseph Marmion senior was the nephew of Dom Columba Marmion OSB, the abbot of the Belgian monastery of Maredsous in Wallonia, a relatively recent Benedictine foundation having been established in 1872. Christened Joseph Aloysius in 1858, the son of an Irish father and French mother, he was educated at Belvedere, and was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 2000. Portraits show that he shared the same kind of large somewhat square head with his grand-nephew.

Photo: Abbaye de Maredsous

Dom Columba adopted as his motto magis prodesse quam non praesse, taken from the Rule of St Benedict and meaning “to serve, not to be served”. He died during an influenza epidemic in 1923, aged 64. His spiritual writings were hugely successful and were translated into many languages. He was considered one of the most influential Catholic teachers of his time.

The father of the Joseph Marmion who concerns us here had been born in 1887 at Pomeroy, Co Tyrone and his early childhood was spent in Dungannon where his father, Surgeon Matthew Cordier Marmion, was a Justice of the Peace and practiced as a doctor. The young Joseph Marmion senior was sent to school at his uncle’s abbey of Maredsous in Belgium from which he proceeded to studies in Dublin, almost certainly at the Cecilia Street medical school (the forerunner of the UCD School of Medicine) and became a Licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland and of the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland (LRSCI and LRCPI) at the age of 22 in 1909.

Having qualified, he spent some time in London, where his uncle, yet another Joseph Marmion, was an eye surgeon, and where he had some post-graduate training in tropical medicine. In 1914 he went to South-East Asia as medical officer to the North Borneo Chartered Company which had administered the area and exploited its natural resources since 1881. He probably deliberately planned for such a career – there were plenty of opportunities throughout the Empire for a young doctor.

Within a few months of his arrival in the Malay Archipelago, World War I broke out and Dr Marmion heeded the call of John Redmond – I’m assuming that as an Ulster Catholic he was more likely to have been a Home Ruler than a Unionist but I may be wrong - and returned to Europe to enlist in the Royal Army Medical Corps where he rose to the rank of captain. His son, the late Tom Marmion, has written that his father’s service in the Great War destroyed his health. On active service throughout the Gallipoli campaign in 1915, he seems to have been injured, returning to Ireland to serve with the Royal Irish Fusiliers at Buncrana, Co Donegal. According to his obituary in the Liverpool Echo, “in 1916 he was sent to France at his own request” and was invalided out of the army in 1918. Perhaps he had been appalled at the 1916 uprising and wanted to support the war effort which after all, had started, at least in theory, in an effort to defend small nations such as Belgium where he had been educated.

After his departure from the army, Ireland was becoming increasingly uncomfortable for men who had served as officers in the British forces and this may well have been the spur to his decision to seek a career elsewhere. Clearly a brave man, he was probably in quite poor physical, and possibly mental, shape by the time he arrived in Liverpool three years later at number 40 Dodge Street. He was 34, and recently married to Brigid Hayes. The first of the Marmions’ children, Teresa Honoria, was born there.

The Dodge Street community was a relatively poor one. Ten years before Dr Marmion’s arrival there the Census shows that the residents included a labourer, railway porter, shop assistant, locksmith and, at number 40, a bootmaker born in Dublin.

The family’s move to Roselands Cottage on Woodlands Road was a considerable step up in social terms. This late 19th century house must have provided an idyllic escape from the inner city grime of Dodge Street. Its privacy and enormous garden stood in sharp contrast to the modest neighbouring redbrick Edwardian terraces. It was acquired from another doctor, presumably along with his practice. Dr Smith had been a bachelor and had lived there alone except for a housekeeper, and the neighbours – in their considerably less extensive properties - included a civil engineer, a head gardener, an insurance clerk, a police sergeant and a house builder.

After the Marmions’ time, the very large garden – a resident gardener is recorded on the 1911 Census - shrank as houses were built on its grounds, initially on Woodlands Road after the War and finally on its Western boundary on North Sudley Road in the 1970s. Roselands Cottage itself survived, shorn of its gardens, until the 1980s. After it was demolished, two nondescript detached houses were built on the shrunken site, accessed from Elmar Road at the back. The only trace that now survives is a short section of the old garden wall.

The Aigburth neighbourhood was solid and respectable, a half hour’s walk from the city centre and a short stroll from the rus in urbe of Sefton Park which had opened to the public in 1867, with its cricket pitch, tennis courts and Victorian palm house. It would have supported a successful medical practice.

The young Joseph Marmion junior started his education with the Faithful Companions of Jesus nuns on Aigburth Drive beside Sefton Park. He was then sent to St Francis Xavier’s College, which was located in Salisbury Street just north of the city centre at that time. It had been founded from Stonyhurst College, the Jesuit public school in the north of Lancashire, in 1842. The current archivist at St Francis Xavier’s, now in much leafier Woolton, was unable to find any record of his early school career. The school magazine is not indexed and, she added, “Unless he was very sporty he probably isn’t going to be mentioned in them either.”

Photo: britishlistedbuildings.co.uk

One of the things we know for certain about Marmion is that he despised sport in all its forms.

Dr Joseph A Marmion died on 10 August 1936 at his home and, contrary to his death notice in the local newspapers, was buried at the Cistercian abbey of Mount St Joseph in Co Tipperary. He was 49, and the young Joseph was 11. Although the family lived in the parish of St Thomas More in Aigburth, they worshipped at St Austin’s, Grassendale, two miles from home, and run by the Benedictine monks of Ampleforth Abbey in Yorkshire. It was here that his funeral Mass was celebrated. Clearly, Dr Marmion was loyal to the religious order that had educated him in Belgium; the Cistercians of Mount St Joseph are descended, in a sense, from the

Photo: Liverpool Echo

Benedictines. At the time of his death, Glenstal Priory (as it was then) was the only active Benedictine house in Ireland, having been founded from Maredsous. Presumably the spaces in its cemetery, unlike that at Mount St Joseph, were confined to members of the monastic community. Mount St Benedict near Gorey, Co Wexford, had been founded from Downside Abbey in Somerset by the eccentric Dom Francis Sweetman. It was an upmarket boys’ school but closed in 1925, although it remained a daughter house of Downside into the 1970s. (Some of the more difficult members of the Downside community would be sent to be “abbot” there in solitary splendour, served by a housekeeper and butler).

At the time of Dr Marmion’s death, Europe was heading inexorably towards war. Mrs Marmion moved to a Victorian terraced house in Buckingham Avenue, closer to Sefton Park, shortly after her husband’s death, and as the spectre of hostilities loomed. Liverpool was to become the most bombed British city outside London, and the Marmions’ first home there, at 40 Dodge Street, was destroyed, along with most of its neighbours, on the night of 28 November 1940. The street no longer exists, its rubble lying under a shopping centre and industrial estate built in the 1970s.

Operation Pied Piper, the evacuation of Liverpool children to small towns and villages in rural Lancashire, Shropshire and north Wales had started in September 1939 but Mrs Marmion decided to move the family to her native Ireland. It would appear that the children were sent in advance while she concluded matters in Liverpool: Joseph to Clongowes Wood College in Co Kildare where he entered Rudiments, or second year, while his sisters and little brother Tom, then only six years of age, went to board in either Dominican College, Cabra or Dominican College, Wicklow. I am unable to say which. From there, Tom would proceed to Glenstal.

Why was Joseph Marmion not sent to Glenstal? The school had opened in 1932 with just seven pupils and it would still have been very small. So, it surely could have accommodated a 13 year old boy? Perhaps it was too expensive or there was considerable urgency in getting Joseph settled into a new school. Perhaps, too, Mrs Marmion was less loyal to the Benedictines than her late husband had been. And, of course, there may have been a Jesuit connection – I am fairly confident that there was, as we shall see later - and Clongowes may have taken an altruistic view of the fatherless Catholic boy from pagan England.

Writing in later life, Tom Marmion remarked that “families often sent their children away to school in those days of difficult travel”, which is not entirely true. Many upper class and upper middle-class families sent their sons away to prep school at the age of seven or even earlier as a matter of course, and it had nothing to do with the difficulties of travel. It was what people like them did. The Marmions differed in social class from their neighbours and the young Marmion was doubtless aware of this from a very early age. It is, perhaps, significant that Joseph Marmion was spoken of, by some fellow Jesuits and many of his pupils, as a snob. The social insecurity caused by his father’s death may have turned him into one.

There can be no doubt that the loss of his father was a traumatic experience for the young Joseph Marmion. Had Dr Marmion lived, had his practice thrived, and given his strong affinity with the Benedictines, his son may well have been sent to Ampleforth. In those days, unlike now, many family doctors could afford the fees at leading public schools. Had he been an Amplefordian he would not have grown up to be the menace he became as an Irish Jesuit. He may have become a Benedictine menace, of course, and we know that Ampleforth has been amply furnished with clerical paedophiles during its history.

Even before Dr Marmion’s early death, family life was probably not easy as he had clearly suffered from ill health for many years. And from his death in 1936 and as the war years approached the family experienced turmoil.

It cannot have been easy for the young Marmion when he arrived at Clongowes Wood College in September 1939, a year later than his schoolfellows, and with a distinctly English accent. For a boy from a modest Liverpool suburb and an urban day school in Everton, Clongowes must have seemed impossibly grand with its long straight avenue of ancient lime trees, medieval castle and extensive imposing buildings.

Clongowes had been Ireland’s leading Catholic boy’s boarding school since its foundation in 1814. In time it would be eclipsed by the parvenu Glenstal, pushing Clongowes into second place in terms of prestige in the minds of those who care about such things.

The young Marmion’s early days at boarding school can hardly have been any fun at all. Now displaced to neutral Ireland and with his friends and, initially at least, his mother, in an England that was at war, this period may have seen the start of the anxiety that would dog him through life. He appears to have spent his five years at Clongowes staying largely below the radar, something that comes as a surprise considering the largeness of his personality as an adult. However, at least one of his contemporaries spoke of his having been a bully. He seems to have taken no part in sport (indeed, he once threw a rugby trophy into a bin) or drama and is mentioned occasionally as a debater, in which his acerbic wit was clearly developing.

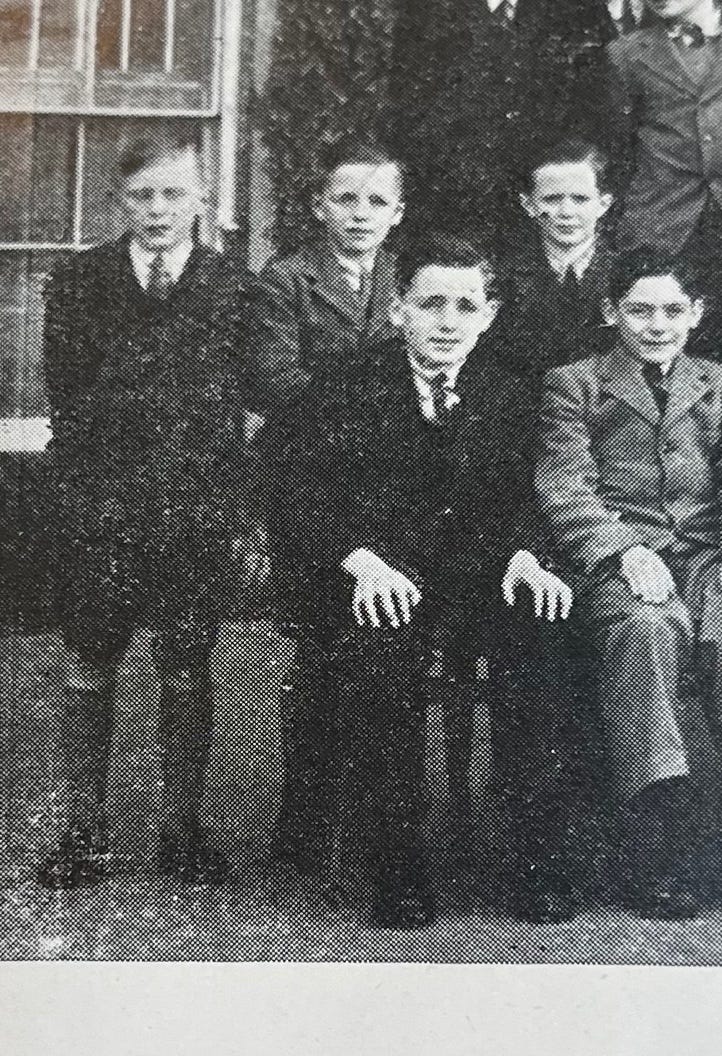

Photo: The Clongownian 1940: J Marmion seated, centre

The recently arrived Marmion “gave a very complete account of Britain’s need for food and raw materials and of how she gives preference to her Colonies’ products,” according to The Clongownian for 1940. Another report, on the Third Line Debating Society, states that “J. MARMION, in what was probably the best-written speech of the evening, was very convincing, as he proved that science had destroyed craftsmanship and had made man a machine.”

Judging by his absence from reports of the various boys’ sodalities in The Clongownian, he was not noted for piety but his proficiency in languages is presaged by a Christmas prize for French when he was in First Syntax (or fourth year) in 1941.

In an account of the school’s production of The Gyspy Baron, by his beloved Strauss, and which he was to produce at both the Crescent and Belvedere, he does not appear in the cast list nor amongst the orchestra.

In his Intermediate Certificate, he achieved honours in English, Latin, French and Mathematics, and passes in Irish, Greek, History and Geography. Curiously, Marmion is not listed in the Leaving Certificate results for his Rhetoric year (sixth year in Jesuit parlance) but he must have sat the matriculation examination for the National University of Ireland.

In Rhetoric he wrote a poem entitled A Concert, suggesting that music was something important to him, that moved him, despite not taking part in such activities in school. It appeared in The Clongownian.

The fourth stanza (of 6) reads:

Now mount we to the stars in flights of song,

Now sink we to the depths with mournful groan

And now the tides of music pour along

And now a lonely violin sings – alone.

And once again with swelling roar and strong

The music seems to reach the very Throne

And once again it sinks back whence it rose,

And with untroubled current onwards flows.

By this point in his school career he must have decided to enter the Jesuit Order. By the following September he had joined 14 other Clongownians, four from his own year, in the Novitiate at Emo Court in County Laois.

Mrs Marmion would live on until 19 March 1962, shortly before her son returned to his old school as Prefect of Studies. She re-joined her husband in Mount St Joseph’s in Co Tipperary a little over half a century after he had been buried there.

Appendix to Chapter Two:

The children of Dr Joseph A Marmion and Mrs Brigid Marmion:

Teresa Honoria, known as Noreen, born 1923, qualified as a doctor, lived and worked in Dublin, unmarried, died 2008. She was buried with her parents in Mount St Joseph’s.

Rosaleen Marmion, born 1924, qualified as a doctor, married 1951, in Liverpool, Dr Henri C. Catsarus, and died in Greece, 1994.

Joseph I Marmion, born 1925, Jesuit priest.

Brigid C B Marmion, known as Benedicta, born 1928, married 1960 John Leo Leahy, lived in Terenure.

Thomas, known as Tom, born 1933, married Bernadette, lived in Kilmacud, Dublin, died 28 June 2021.

Chapter Three: BECOMING A JESUIT 1943-1962

A Man for Others?

-

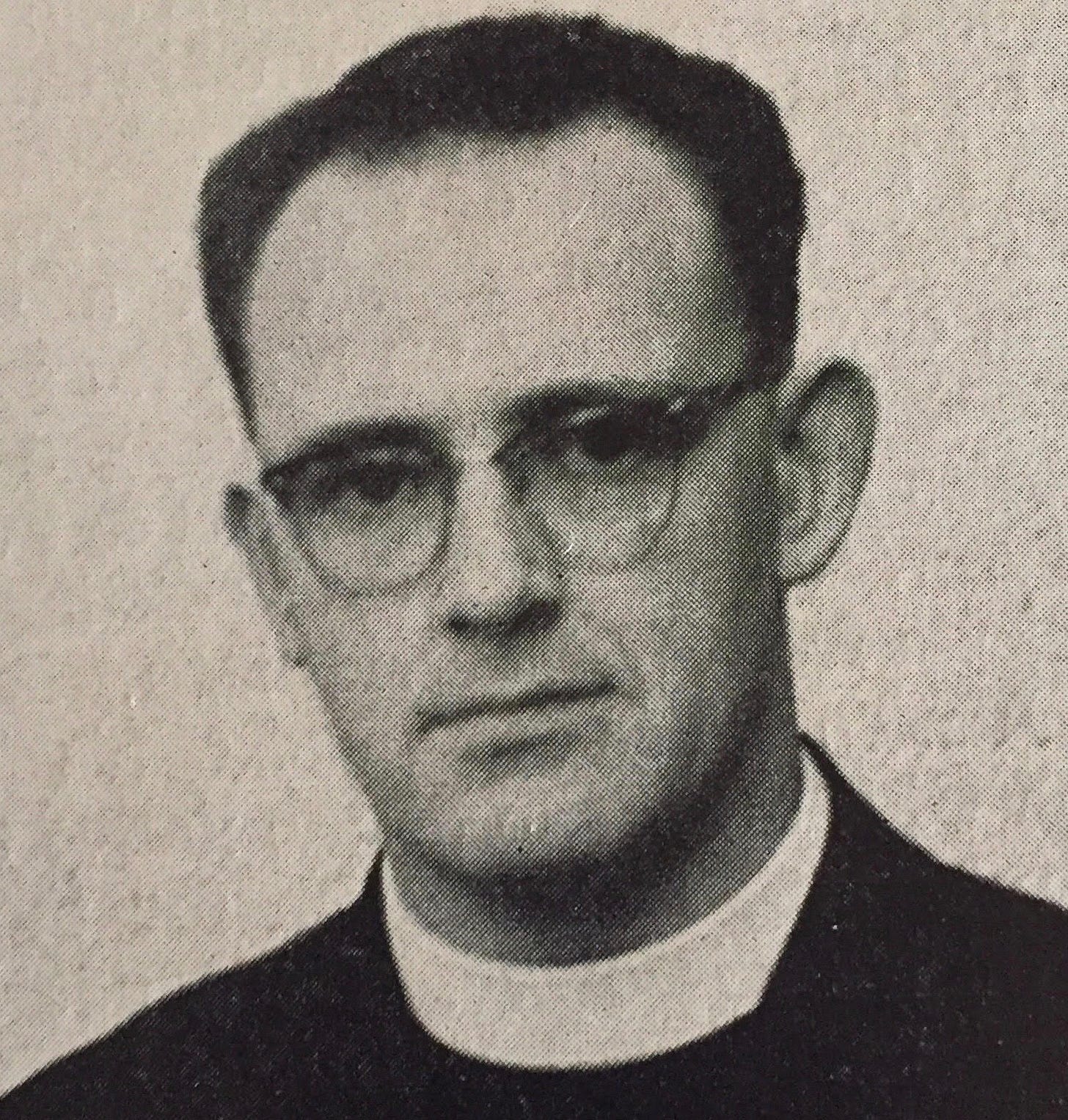

Photo courtesy of Irish Jesuit Provincialate

After the Jesuits finally admitted what Marmion was, the then Provincial, Leonard Moloney SJ, wrote in The Jesuit Response in 2021 “We, who should have protected you, failed you. You, your parents, and families had the right to expect that you would be safe in our care. We failed you in this primary duty and for this I ask your forgiveness. It is my hope that through the restorative processes I, and my Jesuit colleagues, will have the opportunity of making this apology in person. I hope that this response confirms for you the seriousness of our commitment to righting the wrongs and failings of the past.”

The fact is that the Jesuit Order in Ireland failed not just generations of children. They also failed Joseph Marmion in its duty of care. It became apparent, from a very early stage, that he was – at the very least – a troubled person. Warning signals were plainly visible and despite the efforts of several of his superiors, they were ignored.

Why did Marmion want to become a Jesuit? We will never know but can make some informed guesses as to some of the motivating factors. He had had a very unsettled childhood: the loss of his father when he was still a small boy, the coming of War, the vulnerability of his home city to bombing, the family’s uprooting from all that was familiar and the move to Ireland which was, unlike much of Europe, having an “Emergency” rather than a War. He may have sought certainty in religion, the certainty that developed into his extreme conservatism in later life.

We don’t know how much he enjoyed Clongowes; he certainly doesn’t appear to have made much of a mark there but it may have provided a kind of security and a surrogate home. Some Jesuits, conscious of his lack of a father, may have been kind to him. Given that sexual abusers have very often been sexually abused themselves, this may well have happened at Clongowes.

It was a time when many boys, on leaving school, went into training for the priesthood. In a suffocatingly Catholic society, priests were accorded quite unmerited deference and respect. They wielded power and enjoyed considerable status. Then, as now, it provided a sanctuary for boys who knew that they were not attracted to the opposite sex.

In Marmion’s year at school, four boys of the 58 in Rhetoric decided to enter the Jesuit novitiate, including Paul Leonard, the much younger brother of John “Jacko” Leonard SJ, Headmaster of Belvedere, and Paddy Crowe SJ, later a Headmaster of both Clongowes and Belvedere.

Added to this was the cachet of the Jesuits. While most candidates for the seminaries were drawn from the families of small farmers and provincial shopkeepers, the Jesuits recruited almost exclusively from the educated middle classes, especially from schools like Clongowes and Belvedere. Society at large, and some members of the Order, considered the Jesuits to be “a cut above”.

The Jesuits may have had a special interest in the young Marmion on account of his close family relationship to his grand-uncle Dom Columba Marmion who, it was widely thought, was going to be the first saint educated by Jesuits. Dom Columba was officially placed on this trajectory in 1962 and both Marmion, by then Prefect of Studies at Clongowes, and his brother Tom, attended the gruesome business of his exhumation in Maredsous in April 1963. Dom Columba was beatified in 2000 and a celebration was held at Belvedere in honour of this alumnus, at which no mention was made of his grand-nephew’s years at the school. It is supposed that the lengthy process of attaining sainthood will eventually be completed.

We will return to the beatification in due course.

In August 1943, Joseph Marmion, aged 18, was received into the Society of Jesus, straight from Clongowes, by the Provincial, J.R. McMahon SJ, and on 7 September he entered the novitiate at Emo Court in County Laois. In June of that year it was noted by Fr Kelly, the Minister at Clongowes, that “This is a solidly virtuous boy and will, I believe, be a fine man. At present he is, perhaps, inclined to play the buffoon, and babble over with foolish talk etc – but, I think it is merely boyish effervescence and good humour, which on training will tone down to normality”.

Normality is something that Marmion never attained.

His Prefect of Studies, Fr Barrett, wrote at the same time: “Joseph has grown rapidly and though not good at games has much physical energy. He has much mental energy besides, and a very quick tongue. He has suffered a bit from the absence of a father’s strong hand, and his energies are a bit undisciplined. He has been known to argue when he should have obeyed, to work at one thing when he should have been at something else, to be noisy and to annoy his companions with his tongue. For all that he is popular with boys and masters. He is not really ‘difficult’ but rather somewhat undisciplined. He is generous and I believe he will respond to treatment. He has improved this year. I consider him aptus.” In other words acceptable to the Society of Jesus as a novice.

Fr Barrett was nothing if not an optimist.

It's significant that there are two mentions of his “tongue” in just one paragraph. He had clearly been honing it with a mordant sarcasm and caustic wit while still a schoolboy. Marmion’s tongue is what many fellow Jesuits, especially his juniors, came to despise. Of course, in a sporty school like Clongowes, boys who did not excel at games (and Marmion does not appear in a single team photograph during his time there) sometimes gain popularity as wits. In his case he seems not to have distinguished between being amusing and actual cruelty. Or he actually enjoyed cruelty even at this early stage in his life.

In the years before he took his first vows in September 1945 he was considered to be “improving” and that he profited “from correction”. Then, between 1945 and 1948, Marmion moved to Rathfarnham Castle in Dublin, to live with the Jesuit community there while he took an Arts degree at UCD. It rapidly became clear that he was trouble.

A note in his file for 1948 reads:

“Mr. Marmion is hereby warned seriously of the following faults:

1. Lack of religious observance, shown in an habitual carelessness about most of the rules, especially the rule of silence

2. The tone of his correspondence with one of the novices which betrays a deplorable lack of the true spirit of his vocation

3. Repeated admonition has so far resulted in no permanent improvement

He is reminded that unless he sincerely reforms his ways he cannot remain in the Society. As a salutary penance for the above faults, Mr Marmion will spend an hour of prayer before the Blessed Sacrament.”

These comments suggest that Marmion had already decided that he was an exception, one to whom the rules should not apply, that he was somehow special. (Anyone who has read a report from Boris Johnson’s housemaster at Eton will recognise similar themes). The tone of his correspondence with a fellow novice is intriguing. What was it? Did he show disrespect for his superiors? Or was this the kind of “particular friendship” that was outlawed amongst novices? (I have been told he wanted to exchange “snaps”.) One that may have involved a degree of sexual innuendo, the kind of thing that, according to Jesuit colleagues, marked his conversation during his years at Belvedere.

A month after this first warning a letter from the Roman Curia contained the following instruction: “Your Reverence and other Superiors are to be on their guard lest Mr Marmion, a Junior, who ought to be admonished for his failure in religious spirit, should remain for too much longer in that state. If he does not correct himself, stronger remedies will soon have to be applied.”

It is, perhaps, worth remembering that this was the era of Noel Browne’s Health Act 1947, better known as the mother and child scheme, a modest proposal for maternal and child healthcare that was vehemently opposed by both the medical profession and the Roman Catholic church.

Its demolition underlined the fact that the Irish State was in the iron grip of that church. Seán MacBride, the leader of the new Clann na Poblachta party that was to come to power in 1948 on a new republican platform, promising to unite the country and reform politics, wrote to John Charles McQuaid, archbishop of Dublin, on the very day he secured a seat in a by-election “I hasten, as my first act to pay my humble respects to Your Grace, and to place myself at Your Grace’s disposal.”

On becoming Taoiseach he wrote, once again by hand, that as his “first official act” he should “place myself entirely at Your Grace’s disposal”.

This was the Ireland in which Marmion was determined to become a Jesuit, even if it would be, to some extent, on his own terms. He would retain a nostalgia for that Ireland and would remain, until his death, an arch-conservative who was appalled by the reforms of Vatican II, something he shared with “Jacko” Leonard SJ, the brother of his classmate.

Hugh Kelly SJ (1886-1974), a highly cultivated man of letters, was Rector of Rathfarnham Castle during Marmion’s time there and Jesuits interviewed in 2021 recalled that he wanted the sharp-tongued, undisciplined young man “out of the Order”. He was clearly an excellent judge of character. However, they said that Marmion seemed to be protected by a wheelchair-bound senior member of community “to whom Joseph Marmion had apparently shown kindness.”

The only member of the Rathfarnham community at this time who matches the description was Jerry, or Jeremiah, Hayes (1896-1976) who had been at Clongowes with John Charles McQuaid, the authoritarian archbishop of Dublin, and who developed severe arthritis in his early 30s, spending the rest of his life as an invalid. He has been described as one of the more approachable senior members of the Rathfarnham community and as having a good relationship with the juniors, some of whom acted as what he called his “charioteers”. These young men would take him out in the castle grounds and in the locality and it's clear that he enjoyed their company.

His surname may be significant. Marmion’s mother was Brigid Hayes. Was Fr Hayes a relation? I have been unable to establish any connection.

A deeply spiritual man who was accustomed to considerable suffering in the days before chronic arthritis was managed in any even vaguely effective way, he may have been impressed by Marmion’s very close family connection to Dom Columba, one of the most noted spiritual writers of his time. The young Marmion’s “kindness” to Fr Hayes may have been spontaneous and genuine but the fact that he would become a master manipulator of people might suggest that he was already polishing this malign skill. In any event, Fr Kelly seems to have been persuaded, albeit with considerable reluctance, to give Marmion yet another chance.

A Jesuit, who was two years behind Marmion, whilst in formation, recalled that he could not understand how he had got away with his behaviours at this time and why he had not been asked to leave. Asked about these behaviours, he said that Marmion was very noisy, loud and pushy. Hearing of a formation report dated January 1949 which stated "extra experiments might develop and mature him", he explained that such “experiments” in the Novitiate meant that you would be sent down to work for a month in the kitchen, the intention being to train you in humility. There is no record of such an “experiment”, nor indeed any indication that Marmion ever learned humility.

From now until 1951 Marmion moved to the Jesuit house at Tullabeg in Co Carlow (known amongst students as “the bog”). It had been founded in 1818 as a boarding preparatory school for boys and from 1858 a senior school was added; St Stanislaus College, as it was known, had closed 1886, the pupils being moved to Clongowes, and the imposing, rather dreary buildings became a “house of formation and studies” for novices and Tertians, or recently ordained Jesuits. It was here that Marmion, having survived Rathfarnham by the skin of his teeth, was sent to study philosophy. These studies completed, he we was sent back to his old school, Clongowes, as a scholastic teacher (i.e. a yet-to-be-ordained member of the Order).

It was here that he would show his first recorded signs of paedophilia. A Jesuit who was a junior boy at Clongowes at this time recalled in 2021 at least one occasion when small boys, covering themselves only in towels, were running along a corridor near the showers and they were trying to avoid Mr Marmion lest he grab their towels. It seems unlikely that this was the only such example of Marmion’s behaviour in the presence of semi-naked young boys.

It is worth remembering that the word “paedophilia” was only coming into use in psychiatry from the early 1950s and while these days it is generally defined as sexual attraction to prepubescent children, Marmion’s disorder would now be called hebophilia where the sexual attraction is to children between the ages of 11 and 14, depending on the onset of puberty.

It's significant that one of his former pupils has said “He lost intertest in me when I came back in September. My voice had broken during the holidays.”

From Clongowes he went to the Crescent in Limerick where he assisted with the Christmas musicals and ran the junior debating society. The late Sir Terry Wogan, in his autobiography “Is This Me?”, quotes from his diary as a boy at the Crescent, recording that it had not been a good day because “Mr Marmion was in a bad mood.”

There is no record of his behaviour, either in the classroom or in private from this time but Terry Wogan’s schoolboy note suggests that he was not always a ray of sunshine.

From the Crescent he proceeded to Frankfurt for theological studies at the Sankt Georgen Hochschule. During his time there it was reported that he had not learned German well, although able, that he was impulsive and inclined to make critical comments, and lacked self-control. So, no change then.

A Jesuit who studied at the same Frankfurt hochschule as Marmion, but in the 1970s, met another priest who had been a contemporary of Marmion’s there, and has reported that when asked what he had been like, the priest replied “He was as I presume he is now,” implying that he had been, at the very least, a difficult personality.

Despite being a difficult and clearly troubled person, Marmion was ordained priest on 31 July 1957 in Frankfurt and then spent the following year at Rathfarnham for his Tertianship, a kind of long retreat during which the newly minted Jesuit rehearses the spiritual exercises of St Ignatius of Loyola. His Tertian Instructor was his old adversary, Hugh Kelly SJ, who had returned from a spell in St Francis Xavier’s, Gardiner Street. There is no record of how they got on together but, now that Marmion was ordained, there was no going back.

According to one of Marmion’s own letters, written more than a decade later, he had a nervous breakdown during this time at Rathfarnham Castle. The euphemism that Marmion used in correspondence with friends to describe his mental state – of anxiety and depression – was “jim jams”, a phrase most of us associate with childrens’ pyjamas, although it seems to have been a 19th century slang word for delirium tremens or the DTs. In 1969 he wrote to his best friend within the Order – probably Paul Andrews SJ - saying that he had suffered “jim jams” at Rathfarnham and had been treated by a doctor.

Nevertheless, not much more than a year later, the Jesuits saw fit to send him to the Crescent where he remained until 1962 and where he served as choir master, also producing his first operettas.

Then, bizarrely, Marmion was appointed Prefect of Studies at Clongowes, “when I had just recovered [from a nervous breakdown]” as he later recalled. The appointment was not made by the Irish Provincial, as was the usual practice, but by the American “Visitor”, John J McMahon SJ of the New York Province. His other decision, over the head of the Provincial, was to close Tullabeg; neither endeared him to the Irish Jesuit province.

Visitation of this kind has nothing to do with the Feast of the Visitation, when the Virgin Mary, pregnant with Jesus, is supposed to have visited her cousin Elizabeth who was pregnant with John the Baptist. As far as I can gather, a Visitation is an investigation into how Jesuit establishments are performing and may involve recommendations or, indeed, edicts, designed to improve matters. There are domestic visitations, ordered by the Provincial, and those ordered by the Curia which was the kind that McMahon undertook in 1962.

It's important to remember that Marmion’s grand uncle, Dom Columba Marmion, was put on track for sainthood in 1962. This was big news in an overwhelmingly Catholic country and Marmion would have been seen as something of a celebrity amongst the devout.

So much for the facts that can be established. But some anecdotal evidence is worth recounting too.

A former Jesuit has told me that during John J McMahon’s Visitation of Ireland, two Irish Jesuits took him on a trip to the West of Ireland in order to indulge one of his great enthusiasms: fly fishing. The two Jesuits, he says, were Joseph Marmion and William Troddyn. Troddyn was a very keen fisherman and wild fowler but I’ve never heard that Marmion knew one end of a rod from the other. But both men shared a deep conservatism that would soon be outraged by Vatican II. And it was shared by McMahon who, during his Visitation of Australia (he seems to have been to be the go-to man for Visitations) had been outraged that girls took part in dramatic productions at the otherwise all-boys St Ignatius College in Melbourne. I have imagined this coming up in conversation with Marmion and Troddyn on their fishing trip and Marmion, having dressed boys as girls during his time at the Crescent, wholeheartedly endorsing this view. Where, he might have asked, was the fun in girls?

This little break in the West, probably in Waterville where Troddyn regularly visited with rod and flies, became the talk of the Jesuit community in Ireland when McMahon’s two companions were suddenly and – in Marmion’s case at least - completely unexpectedly appointed as Prefects of Studies, Marmion to Clongowes, Troddyn to the Crescent, in July 1962, just a few months after the angling trip.

They had both made catches.

Billy Troddyn SJ, six years older than Marmion, may have been conservative, like Marmion, and somewhat irascible but he seems to have been much liked by the boys at the Crescent.

His obituary, published in 1984, recalls that “he was deeply disturbed by changes in the Church; departures from the priesthood, especially from the Society, which he loved - distressed him a lot; he was less than enthusiastic about non-clerical dress; was reluctant to concelebrate; did not altogether care for prayer-groups and community meetings; and had very radical solutions for muggers, as also for itinerants and their wandering marauding horses. These latter irritated him intensely by their depredations into lawns and gardens, as he was ever a keen gardener and cultivated many varieties of flowers, shrubs and trees.”

I recall his brother, Peter Troddyn SJ, at Belvedere, as a kind and gentle man who used a small silver machine to roll his own cigarettes.

Marmion was now 36 and had lost his mother in March 1962. Still mentally fragile after his nervous breakdown he was probably starting his lifelong dependency on benzodiazepines, Librium being introduced in 1962 as a tranquilliser, Valium following soon afterwards.

Joseph Marmion SJ was about to unleash a reign of terror at Ireland’s oldest Jesuit school, Clongowes Wood College, where the boys first encountered him at the start of term in September.

Appendix to Chapter Three:

Many of Marmion’s early years in the Jesuits were spent in surroundings of architectural splendour. Emo Court, a neo-classical mansion designed by James Gandon, who was also responsible for the Customs House, King’s Inns and Four Courts in Dublin, was started in 1790 but not completed until the 1860s. Originally the seat of the earls of Portarlington, the house and estate was acquired by the Land Commission in 1920 and subsequently sold to the Jesuits in 1930. Between then and 1969 some 500 Jesuits received their initial training there. The Order sold the house and remaining lands to Mr Cholmeley Harrison who commissioned a thorough restoration and presented it to the State in 1994, living in an apartment there until his death in 2008. Many classical statues were recovered from the lake, having been consigned there when the Jesuits acquired the property. Classical nudity, it seems, was not appropriate for young men starting their life of celibacy, at which most of them succeeded. It is in the care of the Office of Public Works and both the house and the 35 hectares gardens are open to the public.

Rathfarnham Castle, originally the seat of the Loftus family (who later moved to Mount Loftus in Co Wexford, supposedly “the most haunted house in Ireland”, was built for Archbishop Adam Loftus in the late sixteenth century. The 18th century interiors are in part by Sir William Chambers. The Jesuits bought the castle and the remains of the original estate in 1913 and sold it in 1986. Since 1987 it has been in the care of the Office of Public Works, has been restored and is open to the public.

Crescent College, correctly Sacred Heart College, was established by the Jesuits in the Georgian crescent in the heart of Limerick in the 1860s and became independent of the local diocese by 1870. It was a day school that occupied several fine 18th century buildings but these had become unsound by the early 1970s and while a move to the recently closed nearby Jesuit boarding school, Mungret College, was considered, it was thought to be too far from the city. In the end, the Crescent became a comprehensive school and moved to Dooradoyle in 1973, becoming the first Jesuit school in Ireland to be co-educational.