Honor Tracy, the English writer who made Ireland her home, wrote in the 1950s about the difficulty in finding anyone in the country who could be described as openly anti-clerical. Eventually, she heard of one such man and took the bus down to Edenderry, or wherever, to interview him. Speaking out about the Roman Catholic church was the surest and quickest way to destroy your career in those days. And it turned out that the “notoriously anti-clerical” fellow would say nothing, so she had a wasted journey.

(She was also sued by Canon O’Connell of Doneraile when she wrote in The Sunday Times about his fund-raising for the parish house. (If you ever wonder if Ireland has truly changed for the better, read this report of a protest in the Cork village.)The newspaper settled out of court for £750 whereupon she sued The Sunday Times for damaging her reputation; she won and got £3,000 damages plus costs. This experience formed the basis of her hilarious, if rather rickety, 1956 novel, The Straight and Narrow Path).

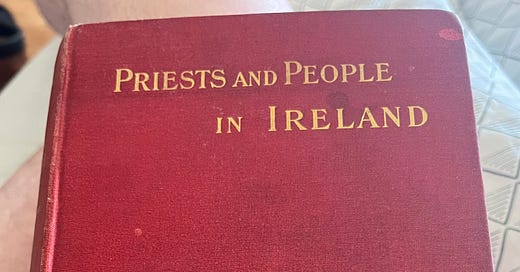

Michael J F McCarthy (1862-1928) was openly anti-clerical. A barrister by profession, he became a best-selling author, earning the wrath of the clergy, for his book Priests and People in Ireland in particular.

The Dictionary of Irish Biography says: “McCarthy had now found his leitmotif: his third book, Priests and people in Ireland (1902), brought him a large audience, selling more than 60,000 copies in a few years. It is a full-scale attack on the catholic clergy, whom he accuses of seeking their own aggrandisement in alliance with an alien organisation; indoctrinating youth; interfering in every sphere of public affairs; embittering Ireland against Britain; and taking the savings of the old and weak.”

Well, that’s a pretty fair summary. McCarthy didn’t take prisoners and while the book can be a stodgy read (and sound a little hysterical at times), one can’t help but be impressed by the passion and anger that informs it. And in terms of hard facts, it is very difficult to argue with his conclusions – but of course many have tried.

He was not born in Midleton, Co Cork, as stated by the DIB. His father had a shop there but McCarthy was born on the family farm at Clonmult a few miles north of the town, beyond the very slightly larger village of Dungourney. He started his education with the Christian Brothers, proceeded to the Vincentians in Cork city and finally ended up in the Church of Ireland Midleton College which his father considered “superior”. Here he became head boy, despite his faith, and went on to Trinity College, Dublin.

He contested a Dublin seat in the Unionist cause and eventually, like so many of that ilk, left Ireland for England where he died. In later life he had become an Anglican. There is no doubt that he was a zealot and that he was obsessed with the church and the damage that he argued it inflicted on the country and its people. However, I can’t but buy his argument.

Here we are in 2025, more than a century after independence was gained. In Peter Lennon’s 1967 film, The Rocky Road to Dublin, he asks the question “what do you do with your revolution once you have it?” Well, you hand it over to the Roman Catholic church.

Of course, it was a process that had started under British rule.

The Society for the Promotion of Education of the Poor in Ireland, (the Kildare Place Society) was set up in 1814 with the aim of providing schools “divested of all sectarian distinctions of Christianity” and was financially supported by the State. The society’s stipulation that the Bible be read to students - without Catholic guidance – was not acceptable to the church. It has always been concerned with guidance, for which read control.

In 1831 a system of national schools was introduced. They were to be interdenominational, and applications were to be made jointly by the religious groups involved. Religious instruction was kept separate from the rest of the curriculum. While the Roman Catholic church agreed to joint applications, there was much Protestant objection, especially from Presbyterians. By 1840, the national schools had become denominational – not Irish Protestantism’s finest hour.

However, provision for children whose parents objected to religious instruction, was enshrined in the new order and later in both Article 8 of the 1922 Constitution and Article 44.4 of the 1937 Constitution.

The separation of religious instruction from the rest of the curriculum worked well until 1971. Indeed, until then religious instruction in national schools took place daily between noon and half-past so that children who needed to leave could do so.

Lobbying by the Roman Catholic hierarchy eventually succeeded in changing all that. New rules introduced in 1971 declared that “the separation of religious and secular instruction into differentiated subject compartments, serves only to throw the whole educational function out of focus”. And so, the church succeeded in changing their national schools into thoroughly denominational institutions in which religion can be brought into any subject that is taught.